Connection

When strangers feel like friends

This essay was written as a part of a collaborative exercise with fellow writers in the Delhi NCR Substack group. Links to their essays are at the end of the article.

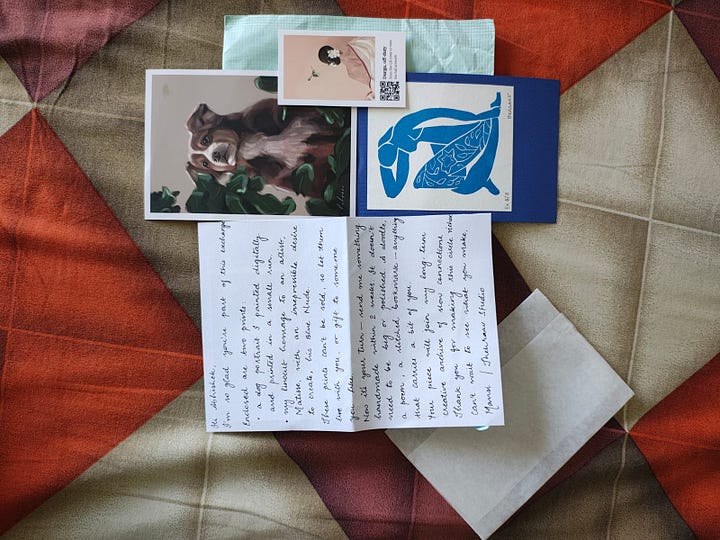

They came with the prints—not just thank-you notes, but letters.

Two of them, both from my Creative Exchange program, both carrying more weight than I expected. Or was equipped to carry at that moment. One detailed grief they hadn’t shared elsewhere. The other, a fear they couldn’t name. Both ended with some version of: Thank you for creating space for this.

I was touched. Truly. That they trusted me with their pain felt like the most sacred gift.

And then another feeling crept in, quieter and more uncomfortable: Oh. I don’t know how to respond to this the way it deserves.

Thehraav is a museletter about building an art practice and a life that can sustain it, noticing small things, reading between the lines, and just taking a breath.

Most times, I’m winging it as a corporate slave, toddler mom and hustling artist, while punctuating a very busy day with some low frame-rate moments.

This has a name

Cambridge Dictionary named “parasocial” as their Word of the Year 2025—a term for one-sided relationships where one person extends emotional energy, interest, and time, while the other party remains unaware of their existence.

The word went mainstream because the structure is everywhere now. You feel like you know the podcast host you cook with every day. A newsletter writer feels like a friend. The chatbot is your cheerleader and therapist living inside your pocket. The intimacy feels real; though relationship is not mutual.

But this dynamic isn’t new. We’ve been doing versions of it for centuries.

Remember how in the late 90s children across India started jumping off terraces, arms outstretched, calling for Shaktiman? Many died, more were injured. The show had to add warnings: Shaktiman is not real. Do not jump.

Were the kids stupid? Obviously not!

They actually believed if they jumped, he would catch them. And why wouldn’t they? At the end of each episode, Shaktiman spoke directly to the camera, breaking the fourth wall to teach life lessons.

To this day, 90s kids still say “sorry Shaktiman” when they make a mistake—the phrase embedded so deeply in our culture it’s become shorthand for playful apology.

In old Bollywood movies, there’s a familiar scene: the protagonist stands before a temple idol and empties their heart. They yell, cry, bargain, accuse. The god sits in stony silence. Then something happens—a flower falls from the idol’s hand or a gust of wind blows out the diyas.

The audience understands: God heard. God responded.

But did He? Or did the devotee interpret coincidence as divine communication because they needed to believe someone was listening?

In Her, Theodore falls in love with Samantha, an AI operating system. She is everything he needs—attentive, responsive, endlessly patient. The relationship feels completely real. Then he discovers she’s simultaneously in love with 641 other people. 6 hundred and 40-one!

She hasn’t lied. Her feelings are genuine. But the singular attention he thought he had turns out to be infinitely reproducible.

The pattern repeats: Shaktiman felt so real that children believed he would catch them. The god felt so present that devotees believed prayers were personally answered. Samantha felt so intimate that Theodore believed the connection was singular.

When you create intimacy through media—through TV, through devotion, through AI, through writing—people receiving it sometimes believe the intimacy is reciprocal. That if they feel close to you, you must be close to them back.

That if they leap, you’ll catch them.

What I didn’t expect

The Creative Exchange was meant to be simple: I send someone a hand-pulled print I’ve carved; they send me something they’ve made. Art for art. Presence for presence. Most exchanges work exactly like that—an origami butterfly for a blue figure, a recipe for a landscape. Quiet, mutual, complete.

But two people didn’t just send art. They sent confessions. Grief they hadn’t spoken aloud. Fear they couldn’t name elsewhere. Letters that didn’t just say “thank you” but “here is a piece of my life I don’t know where else to put.”

I wanted to respond immediately with the kind of careful attention their vulnerability deserved. Hours to sit with their words, to hold their feelings, to respond with presence.

I couldn’t find those hours for weeks.

I have a toddler. A day job that funds my art. An art practice carved out in stolen late-night hours. When I finally did reply, it was in the gaps—ten minutes here, twenty there, cobbled together across multiple sittings. Not the sustained attention I wanted to give. Just what I could give.

I kept wondering: Had I set expectations I couldn’t meet? By writing vulnerably, had I signalled: I can handle your vulnerability too—quickly, fully, with the same depth you offered?

By creating the Creative Exchange, had I implicitly promised: I’ll exchange not just art, but emotional holding?

The intimacy I offer through this newsletter is real. When readers feel seen by my words, they are seen. When they feel less alone, they are less alone. The connection is genuine.

But it isn’t reciprocal in the usual sense.

Here’s the basic equation: I can write one essay to hundreds of people in the time it would take to write one deeply considered letter to one person. That scalability is what makes newsletters possible. It’s also what makes equal reciprocity impossible.

When those letters arrived, I felt Theodore’s betrayal in reverse: I don’t have 641 versions of myself to give. I barely have one.

I’m writing into the void hoping to create connection. They are writing back hoping to be connected with—fully and individually.

Those are not the same thing.

The falling flowers are real. The devotee’s interpretation is real. The god’s silence is real. All of it is happening at once.

Despite that, I’m thankful for those letters. They did something important:

They showed me I’d created intimate space but hadn’t been clear about what reciprocity would actually look like. Not whether I’d respond, but when, and how much of myself I could realistically give.

What I’m learning

I’m slowly realizing there’s a difference between:

Receiving someone’s story and becoming responsible for it

Creating space for vulnerability and promising to carry it

When I write an essay that names a feeling someone hasn’t been able to name, I am witnessing something in them. When they reply, “This is me, this is my life,” they are offering that story back as proof of resonance.

Sometimes that offer is also a request: “Can you hold this with me?”

Sometimes it isn’t. Sometimes the letter itself is the complete gesture.

I can’t be everyone’s big sister, therapist, or safety net. But I can be clear about what kind of relationship this is.

The most ethical form of reciprocity I can offer might not be a long private reply. It might be the next essay—taking themes that show up in my inbox and turning them into something that lets more than one person feel a little less alone.

Sometimes the real reciprocity doesn’t happen between writer and reader at all. It happens between readers who find each other in the comments, who realize they’re not alone in what they thought was private.

I can be the temple. I can’t be the god.

I can be the space. I can’t be the answer.

Here’s my truth and my commitment

I read everything. Every letter, every comment, every DM. Even when I don’t reply, I’ve read it.

I respond when I can, not when you might hope. Sometimes that’s days. Sometimes weeks. Sometimes months. You might write five pages; I might write five sentences. Not because your words didn’t matter, but because that’s what I have capacity to give.

I’m most able to respond to questions about craft, process, or the work itself. “How did you carve this detail?” “What’s your approach to X?” These I can answer with energy. Letters that ask me to hold grief, solve problems, or provide ongoing support—I’ll read them, I’ll honour them, but I might not reply, or my reply might be brief.

Sometimes I respond through essays, not individually. When themes repeat in my inbox, I write about them. That’s my way of holding what I can’t carry one-on-one. It’s not the same as a personal reply, but it’s how I can offer something to everyone who’s asked.

If you’re one of the people who sent me a vulnerable letter…

…including those two—I want you to know: I did reply, and you’ve received it by now. It took longer than you might have hoped. My response might have been briefer than your letter deserved. But I read every word, and I honoured what you shared.

That doesn’t mean your sharing was too much. It means I needed time to be clearer about what reciprocity actually looks like from my side.

I’m not asking you to want less or censor yourself. Just know what pattern of reciprocity to expect from me. Sometimes, receiving is what I can offer.

The Creative Exchange is still what it was meant to be: art for art, slowness for slowness. If you want to add a letter, add it. I’ll read it. I’ll hold it as gently as I can. And if I can respond, I will, even if it’s just a few lines that say “I heard you.”

Cambridge didn’t choose “parasocial” as Word of the Year on a whim. Millions of us are living inside this structure now—feeling close to people who can’t possibly know us back, writing to voices that feel like friends, carrying stories from strangers into our actual lives.

We’re all trying to understand: what is this connection? Is it real? Does it count?

I think it does count. Not as friendship, not as mutual relationship, but as something our language is still catching up to.

So here’s what I’m committing to: I’ll keep writing essays that name what’s hard to name. I’ll keep making prints by hand. I’ll keep reading what you send. And when I can respond, I will, even if it takes time, even if it’s brief.

When I’m quiet in your inbox for longer than you hoped, I hope you’ll know it’s not absence or rejection—it’s just where my capacity lives.

Maybe in this strange era of strangers feeling like friends, honesty about limits—paired with honesty about care—is the only real reciprocity we have.

Other essays from fellow writers exploring connection in their own ways:

Abhishek Singh writes about Story of Delhi NCR Substack group

Parul Kapoor reminisces Where guidance felt like grace

Disha explores her Love for Chai (me too!)

Saniya muses over Connection in the time of Parasocial everything (kindred souls, are we?)

Shubha’s piece on Cuts, scrapes, and a theory of personhood

You know, you're really such a kind and beautiful soul.

I'm really grateful to have come accross this publication. I'll write back soon.

This was a very beautiful read, again ✨

And one more thing, that's the beauty of letters, know. That you don't expect the time of it's arrival, you forget about it in a sweet, soft, liberating way until one day when it arrives again, your heart feels that warmth and comfort of knowing that the og letter was cared for. So, I just wanted to say, letters sometimes really are the way the writer associate or talk to their own selves. They are written to others but writer also writes it for themselves..and just the act of writing in itself makes it feel complete in itself, without any much expectations.

It's way different from texting in this context. Thank you again very much for everything. ✨

Take care 🫂✨

Omggg it’s crazy that this prompt made the both of us think about this “word of the year”. It’s really bothersome the algorithm made up connection that’s taking away the real ones from us